Mining is an industry with very obvious cyclical characteristics, with huge investment and highly influenced and constrained by downstream demand.

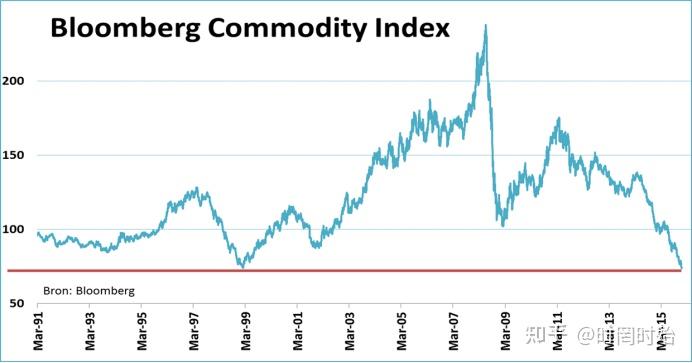

From the 2000s to the early 2010s, with the development of global economic globalization, China's accession to the WTO, and the subsequent comprehensive rise of the Chinese economy and the improvement of urbanization level, the demand for commodities in the global market has been increasing year by year, and the prices of commodities have been rising all the way (see figure).

The global mining industry believes that such strong demand will continue, so they have increased their investment and inevitably incurred huge debts in the process. According to data from PwC, the mining investment frenzy reached its peak in 2013, with the world's top 40 mining companies having a total capital expenditure of $130 billion that year, accounting for almost four fifths of their EBITDA.

EBITDA is a financial term that represents a company's profitability indicator, meaning "earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization". EBITDA excludes the aforementioned non operational factors and can better reflect the company's operating conditions.

After entering the 2010s, global economic growth slowed down, and as the world's factory, China's demand for commodities, especially various mineral products, weakened, leading to a sharp decline in commodity prices and industry profits. Therefore, since 2013, mining groups have been struggling for a decade, mostly trying to balance their balance sheets.

In 2015 alone, global mining reduced assets by over $50 billion. Write down assets refers to reducing the value of a company's assets to a value lower than the original purchase cost. Write downs are usually made due to a decrease in asset value or an expected inability to achieve expected returns, which naturally have a significant negative impact on the company's financial condition.

Starting from BHP Billiton, the world's largest mining company, mining companies of all sizes are divesting some of their mining assets to recoup funds and streamline their large business systems. Most of the recovered cash is used to repay debts, rather than developing new projects.

As can be seen from the figure below, since 2015, the prices of commodities have begun to recover, and the profit level of the industry is bound to rise synchronously, but investment has not recovered. In 2022, the 40 largest mining companies invested a total of $75 billion, which is only a quarter of their EBITDA. For the whole year of 2023, BHP's investment amount is approximately $7 billion, which is only one-third of the peak investment amount in 2013.

But this situation may soon reverse.

According to the think tank Energy Transition Committee, the decarbonization of the global economy, including a comprehensive energy transition, will require 6.5 billion tons of metals between now and 2050. At present, the lithium and nickel required in batteries are highly concerned, but in fact, they are only a small part of the total demand.

From wind turbines used in wind power to electric vehicles, an additional massive amount of steel is produced every year, which is several times the current global production. This puts higher demands on the production of iron ore; Similarly, expanding and upgrading the power grid will require a large amount of copper and aluminum; In addition, the demand for small metals such as graphite and even platinum will significantly increase.

The world is waiting for the outbreak of mining, and the sooner the better. However, from the current perspective, the mining industry has not fully recovered from the downward trend of the previous cycle.

Firstly, objectively speaking, the current profit margin (return rate) of the mining industry is still relatively low.

The composite index tracking the stock prices of the industry has risen by about 10% in the past decade, while the overall increase in global stock markets has doubled, with the US stock market going even further. In this situation, it is difficult for mining companies to directly raise funds in the stock market.

At present, the return rate of new projects in the mining industry is about 7%. Since the Federal Reserve sharply raised interest rates in 2022, the entire interest rate level has been raised, and the yield of the US one-year treasury bond bond has reached 5%. How can mining companies issue bonds to finance in the bond market.

Without financing channels, capital investment cannot be made. So, now listed mining companies are not in a hurry to raise funds, but instead are giving back cash to old shareholders through dividends and buybacks.

This problem may only be solved after the supply-demand imbalance, the sharp rise in commodity prices, and the overall profit margin of the mining industry rise to a certain extent.

Secondly, the cost of developing new projects has significantly increased, and investment decisions must be made with utmost caution.

All mining companies have stated that in recent years, due to global inflation, labor and equipment costs have generally risen, squeezing profits. The Quebrada Blanca 2 copper mine in Chile, which opened last year by Canadian mining giant Teck Resources, had a development cost of up to $9 billion, almost double the amount planned in 2019.

In addition to inflation, environmental costs are also soaring.

The measures that mining companies must implement to minimize the environmental impact of mining operations are becoming increasingly complex.

In the past, electricity in mining areas could be easily generated by diesel generators; Nowadays, more and more mining companies are being told to either connect to the power grid or install renewable energy such as photovoltaics in their mining areas. Mining and extraction also bring water pollution problems, and local governments require mining companies to solve them. Some places even have to build seawater desalination plants.

All these environmental pressures have further increased costs.

Thirdly, the approval process for licenses by governments around the world is becoming increasingly complex and time-consuming.

Taking the United States as an example, obtaining a license usually takes 7 to 10 years, and companies need to consult various government agencies and other stakeholders. In some places, the elected government is completely powerless to respond to public opposition and simply revokes project permits.

The long approval time is relatively controllable, and the license may be interrupted at any time, which not only delays the project but also increases uncertainty. For enterprises, uncertainty is the biggest cost, and it is the cost of veto power.

At present, new mining sites around the world are becoming increasingly remote, far away from big cities, and deep into indigenous reserves or natural resource reserves. The pressure of protecting natural and cultural historical resources is very high, which is a cost for enterprises. So, mining companies would rather tap into the potential of old mines than develop new ones.

Fourthly, due to geopolitical considerations, mining companies also face political risks.

Western governments are shocked by China's demonstrated strength in energy transition, believing that certain small metals related to energy transition have been controlled by China. Therefore, they have begun to adopt political and diplomatic measures, establishing alliances to safeguard so-called "industrial security".

In 2022, the United States established the Mineral Security Partnership (MSP) with multiple allies to guide investment into the mining and processing of critical metals.

In this situation, the cooperation between Western mining companies and their Chinese counterparts, whether in investment, technology, or development, will encounter more uncertainty.

In recent years, there has also been a bright spot in the mining industry: with the retreat of Western mining companies, companies from emerging economies have begun to flock in, with Gulf economies being a typical example.

The UAE mining company International Resources Holdings is acquiring a 51% stake in Zambian copper miner Mopani for $1.1 billion. The UAE government has agreed to invest $1.9 billion to develop at least four mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 2023, Saudi Arabia's mining fund Manara Minerals is seeking more investment after acquiring the base metals division of Brazil's Vale, the world's second-largest mining company, for $3 billion.

The Saudi government is also exploring mineral resources in its vast desert and opening up to foreign miners. By supporting infrastructure construction such as railways and seawater desalination plants, exempting tariffs on imported machinery and raw materials, reducing license and royalty fees, providing national wage support and rental subsidies, Saudi Arabia is striving to attract mining companies from around the world to come and develop.

Saudi Arabia has invested $180 million to encourage exploration, and has also invested $700 million to create geological maps and establish a resource database. The Saudi government estimates that the mineral resources buried underground, including gold, copper, and zinc mines, are worth approximately $2.5 trillion. This is quite astonishing data, as Saudi Arabia's oil wealth is only $20 trillion at current prices. So, Saudi Arabia's opening of the mining market is a great benefit for the global mining industry.

From January 9th to 11th, mining ministers and executives from around 80 countries gathered in Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, to participate in the country's "Future Minerals" forum and exhibition. It is expected that the forum will reach deals worth $20 billion, highlighting Saudi Arabia's determination to open up its mining market.

Saudi Arabia's investment has paid off, as its developed phosphate mines are locally processed into ammonia and fertilizers, which are then sold to Brazil, Africa, India, and Bangladesh before finally reaching the hands of farmers. The state-owned mining company responsible for the project stated that farmers who use Saudi phosphate plant 10% of the world's food. The company has a large scale, with sales and domestic investment equivalent to approximately 2% of Saudi Arabia's non oil GDP. Another similar project will soon begin production, with an investment equivalent to 1% of non oil GDP.

Except for the Gulf countries, economies in Africa and Asia also have high hopes for mining and subsequent precision processing industries. African governments say that for decades, outsiders have been transporting resources to Africa without promoting its development. Therefore, they insist that this time, economic benefits should benefit Africa.

Simply put, it means' not just mining ore and transporting it away ', but investing locally and carrying out processing and production as much as possible to promote local economic output. The demands of developing economies are completely understandable and legitimate.

For an economy like China, which has complete resources from mining to processing, from equipment to technology, from investment to talent, the opportunities for cooperation far outweigh the challenges.